March 25

On the letterhead of the Department of Fine Arts of Wells College, in the Finger Lakes country of New York State, Victor Hammer wrote to his friend, Howard Coggeshall, the Utica printer, on this date in 1946 and enclosed some specimens of his recent printing at the Wells College Press. The outstanding item was A Dialogue of the Uncial, set in the then new American Uncial type designed by Hammer and printed by hand on dampened Van Gelder paper. In the dialogue a printer (Hammer) converses with a paleographer on letterforms and the craft of printing.

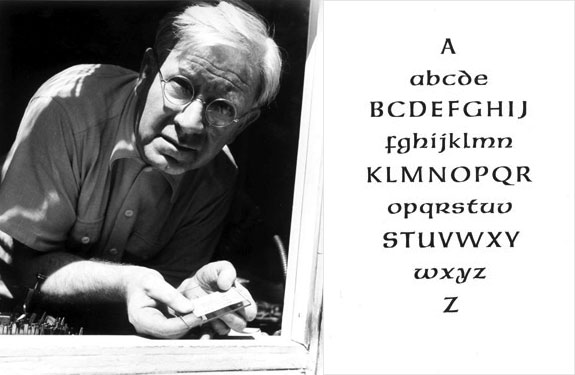

An anachronism in the modern world of automation, Hammer is a craftsman in the medieval sense, believing in the work of the hand rather than the product of the machine. Unlike many men of similar beliefs, Hammer does not advocate this method as an antidote to the tensions of modern life, but merely as one individual’s approach to softening their impact.

The Dialogue begins with the paleographer coming into the printing office where the printer and his son are at work. “Good evening, gentlemen,” he remarks. “It is rather late, I know, but perhaps the best time for me to call at that, for I shall not interrupt you at your work. Would you be so kind as to show me the proofs of your new uncial type-face you spoke of the last time we met?’

“You are most welcome, professor,” the printer answers, “and just in time, too; we have now finished the make-ready and are about to pull a few proofs on the very paper we shall use for the keepsake we are going to print. . . .”

“All right,” said the paleographer. “I want to know more about the other specimen cuttings you made. . . .”

“Well, it began with my first year in this country. I approached the director of one of the biggest type foundries. He showed real interest in my uncial; so I cut a 14-point alphabet and then he had a trial cast made of about 25 letters. With a few pounds of this type we printed a kind of specimen. At the same time my son here had also reached this country, and we began our work at the newly founded Wells College Press.”

“I have never seen this type-face, have I?” asked the paleographer.

“No,” replied the printer, “it was supposed to be impractical; the director felt there would be no money in it. Consequently it had to be abandoned.”

The printer and the paleographer then go on to discuss the qualities of the new uncial form, which the paleographer calls a mongrel, to which the printer asks, “Do you think I would be foolish enough to copy a hand from an old script and use it for printing modern languages?” He then produced a two-paragraph statement which had been printed for the purpose of stating his philosophy as a designer of type:

“Language being itself a means of communication in the ordinary sense, as well as a Pegasus on whom we may ride to heaven, has two distinct aspects: a qualitative and a quantitative; sacred language and profane language. Sacred language is forever seeking to fix the expressive forms of the language by an act of creation; profane language, rich with life and change, is forever bringing the language to that point where a new act of creation is required. Sacred language, the language of the poet, defines these changes and registers them. It is this language, indeed, which determines the change of the visual form of the written or, in our day, the printed word.

“Here as I see it, the type-designer’s work begins. It is not the reader and his demands that I wish to satisfy, any more than it is the writer. It is my conviction that the type-designer should do his work in the service of language.”